April 1, 2025

2025 Apple Industry Outlook: Headwinds Persist in the U.S.

Volume 19, Issue 4

April 2025

Contributed by Chris Gerlach, Vice President, Insights & Analytics, USApple

Coming Off a Tough Year

The U.S. is getting really good at growing, storing, packing and selling apples. Last season, production levels reached all-time highs, topping 289 million bushels.1 This milestone was achieved thanks to several factors including net acreage growth, densification, yield improvements and fair weather. Advancements in state-of-the-art storage facilities and sorting technologies ensured that a greater percentage of those apples found their way into the fresh market.

At the same time the U.S. was recording record-high supplies of fresh apples, demand was falling. Foreign demand for fresh apple exports was 13% below its peak a decade ago.2 Domestic demand was also waning as per capita fresh apple consumption has decreased by 2.2 pounds per person since the 1990s.3 While that may not seem like a lot, it’s equivalent to the combined production of Pennsylvania and Virginia.

These supply and demand imbalances severely disrupted the 2023/24 U.S. apple season causing prices to plummet. For some varieties like Honeycrisp, the prices many growers were being paid were below the cost of production. One in-depth analysis of Washington growers found that 99% of last season’s net returns (revenues less storage, packing and sales fees) went to covering the cost of labor leaving nothing left for fertilizer, loan payments or profit.4

Now, as prices start to recover somewhat this season and exports begin to make up lost ground, the U.S. apple industry is bracing for yet another significant blow: tariffs. At the time of writing this in early March 2025, the trade war is on, but it may be off-again and then back on-again for some time. With this degree of uncertainty, it is impossible to predict the full extent of the impact to American apple growers, processors, importers and the U.S. economy at-large.

The following analysis takes a close look at the current relationships between the U.S. apple industry and some of our most important trading partners: Mexico, Canada and China. The figures detail the size and make up of these cross-border flows that may be at risk in the event of a real, or even threatened, reciprocal trade war. The first section highlights the implications of higher import costs for foreign apples, apple products and a number of other “competitive” produce items. The second section highlights the implications of reduced apple export volumes due to increased costs abroad. But, before we get to that …

Tariffs: The Basics

For clarity, we’ll take a minute to quickly review how tariffs work.

The following bullet points lay out a relatively predictable chain of events that begins the moment the U.S. government places a tariff (tax) on a good being imported into the country.

Direct Effects

- U.S. government places tariffs (taxes) on goods imported from foreign countries;

- U.S. companies importing goods pay tariff (tax) to U.S. government and reduce buying;

- U.S. companies pass along cost of tariff (tax) to their retailers or end consumers;

- U.S. retailers pass along higher costs to consumers in order to maintain margins;

- U.S. consumers face higher retail prices and are left to ultimately pay the tariff (tax).

Indirect Effects

- Foreign governments place “retaliatory” tariffs (taxes) on goods imported from U.S.;

- Foreign companies, now forced to pay higher costs for U.S. goods, stop buying U.S. goods;

- U.S. companies lose export sales, goods stay on-shore and compete domestically;

- U.S. retailers leverage excess supply and minimize costs by paying low prices to producers;

- U.S. retailers may pass along some of those savings to consumers in the form of lower prices.

The remaining sections cover these two stages in more depth, running through the implications of these shifts in supply and prices as well as detailing the extent of the U.S. apple industry’s exposure to international trade – particularly from Mexico, Canada and China.

Direct Effects

As outlined above, once the tariff is in place, U.S. companies importing the newly taxed goods will significantly reduce their purchases from these countries, limiting supply domestically and, in many cases, driving prices up.

This impacts the U.S. apple industry in two primary ways: first, it makes the cost of imported apples and apple products more expensive; second, it makes the cost of other produce imported from places with tariffs – specifically, Mexico, Canada or China – more expensive. We’ll handle each of these in turn.

On the fresh side, the U.S. is a net exporter of apples. That is, we export far more fresh apples than we import. But we do import some and, under the current circumstances, those would be subject tariffs on Mexico, China and especially Canada.

On the processing side, the U.S. is a net importer of apple-related products. Here, the U.S. is especially reliant on China. The following table identifies the value of both fresh and processed apple-product imports for all three of these critical trading partners. It further highlights the amount of tariff – additional tax – that would be levied on U.S. companies if trading volumes remained consistent.

Table 1: U.S. Apple Imports & Tariffs* by Select Countries (2023)

Source: UN, FAOSTAT; USApple

* Tariff revenue based on 25% import duties from Mexico and Canada and 20% from China. These levels assume no change in trading volume.

As the data in Table 1 shows, the U.S. apple industry has some degree of exposure to these direct effects. Clearly, these import levels will decline as U.S. companies shift to other suppliers – if possible. The easier it is to shift, the less disruptive it is to price changes. If for instance, importers of Chinese apple juice concentrate can just as easily buy juice from Türkiye or Poland without a tax, they will do so and things will stay relatively stable. In an ideal scenario, U.S. juice makers would switch at least some of those purchases to domestic suppliers further helping to limit supply at home.

On the fresh side, it is unclear if the partnerships that U.S. importers/sales desks have with their foreign counterparts allow them to quickly and easily amend those arrangements. Assuming that it will likely be a bit more complicated than sourcing low-cost juice, it may be fair to say that decreased imports could “help” the retail price of fresh apples.

At least that would be the case in a country where there was not already an ample domestic supply. As it happens, U.S. production in 2024/25 is down only 3% from last year’s record crop. At around 280 million bushels, the volume dwarfs the 1.3 million bushels imported from these three countries in 2023. These imports are enough to make the difference for some, but a drop in the bucket overall.

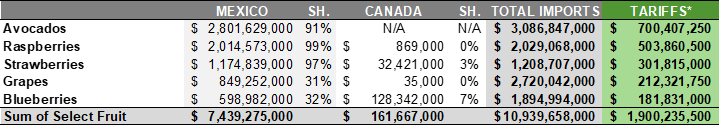

Not all produce items, however, have robust domestic supply. For many, like berries, grapes and especially avocados, the U.S. imports far more than it produces to satisfy domestic demand. In those cases, prices will rise – which may not be a bad thing from the perspective of the competition (i.e. apples). Table 2 details the level of imports and estimated tariffs for five select fresh fruits with particular exposure to trade disruptions from Mexico and Canada.

Table 2: U.S. Fresh Fruit Imports & Tariffs* by Select Countries (2023)

Source: UN, FAOSTAT; USApple

* Tariff revenue based on 25% import duties from Mexico and Canada. These levels assume no change in trading volume.

As the data shows, Mexico supplies the U.S. with 91% of its avocado imports, 97% of its strawberry imports and 99% of its raspberry imports. Switching sources quickly will not be an option and so the supply of these products will fall and prices will rise. While this will make apples relatively less expensive, it is unclear the extent to which customers will shift their purchasing dollars towards apples versus some other competitive product. In theory though, it should drive at least some new apple consumption. Whether those are new customers or more frequent customers, it is an opportunity to remind consumers about the quality, consistency and affordability of U.S. apples.

Indirect Effects

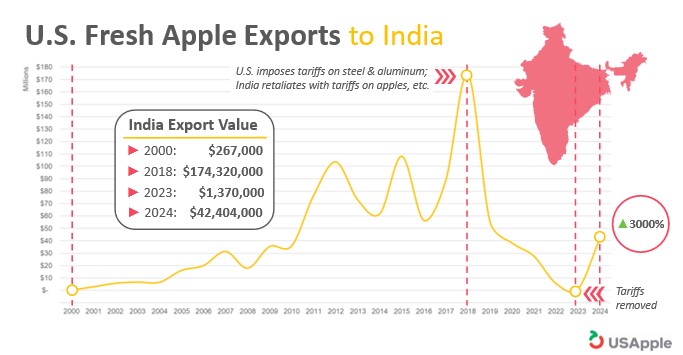

Again, once the U.S. tariffs are in place, a targeted country can, and likely will, respond with trade protections of their own. The U.S. apple industry had front row seats to the last trade war in 2018 when India – America’s second largest export market worth almost $175 million annually – increased their tariffs on our fruit and decimated a market that took 20 years to build (see Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Source: USDA, FAS; USApple

Losing the Indian market in a few short years was not an easy pivot for the industry. Those apples, nearly 8 million bushels, quickly stayed in the domestic market putting pressure on prices at a time of rapidly growing costs for labor and other inputs.

As shown, the Indian market has started to come back a bit since the additional tariffs were removed, but while the U.S. was away, Türkiye and Iran stepped in to take those sales. Given the disparity in labor and transportation costs between the U.S. and these global competitors, it is unlikely that India will be a market easily rewon.5

At stake now are Mexico and Canda, the number one and two fresh apple markets for U.S. exports.6 Figures 2 and 3 detail the size and importance of these two markets alone.

Figure 2:

Figure 3:

Sources: USDA, FAS; USApple Sources: USDA, FAS; USApple

Total (potential) export losses would be around 25 million bushels, valued at more than $550 million annually. That’s a Michigan-sized crop that could theoretically be staying on shore and competing with the domestic supply.

For both Mexico and Canada, Washington dominates U.S. exports, accounting for around 75% of fresh apple shipments to those countries. For Washington, that would mean having to find a new home for up to 20 million bushels. Figures 4 and 5 disaggregate Washington exports to Mexico and Canda by variety.

Figure 4:

Figure 5:

Sources: WSTFA; USApple Sources: WSTFA; USApple

Galas and Red Delicious make up more than 60% of what Mexico buys from Washington. Canada also brings in Washington Galas, but they prefer the Other, typically higher-value varieties including Honeycrisp. These would be the varieties repatriated into domestic supply.

As stated above, with such uncertainty around tariffs and reciprocal tariffs, it’s impossible to know how these trade policies will ultimately impact the U.S. apple industry. One thing is certain, there will be more apples here at home that will push prices down for the second consecutive year.

Where do we go from here?

Obviously opening new export markets is attractive, but that will only go part of the way to replacing our two largest trading partners. Domestic demand must increase. With supportive retail partners we may be able to move volume to make up for lower prices, but it can’t be at the expense of the grower. Margins need to be shared to ensure the long-term sustainability of suppliers. If, and when, avocados, berries and grapes become relatively more expensive, the U.S. apple industry needs to be ready to grab some of those consumers and get them reintroduced to the quality, consistency and affordability of apples – homegrown, delicious and nutritious.

Editor: Chris Laughton

Contributors: Chris Gerlach

View previous editions of the KEP

Farm Credit East Disclaimer: The information provided in this communication/newsletter is not intended to be investment, tax, or legal advice and should not be relied upon by recipients for such purposes. Farm Credit East does not make any representation or warranty regarding the content, and disclaims any responsibility for the information, materials, third-party opinions, and data included in this report. In no event will Farm Credit East be liable for any decision made or actions taken by any person or persons relying on the information contained in this report.

WEBINAR: 2025 Apple Industry Outlook Webinar

Thursday, April 17, 2025, from 12:00-1:00 PM EDT

Join Farm Credit East and Chris Gerlach of U.S. Apple Association to discuss the future of the apple industry, taking a deep dive into the prevailing trends shaping the industry with the opportunity for attendees to ask questions.

This webinar is free and open to all and will be recorded.

Tags: apple, outlook, ag economy, export, fruit